2015年10月27日

A Potluck for the Only Street in Paris

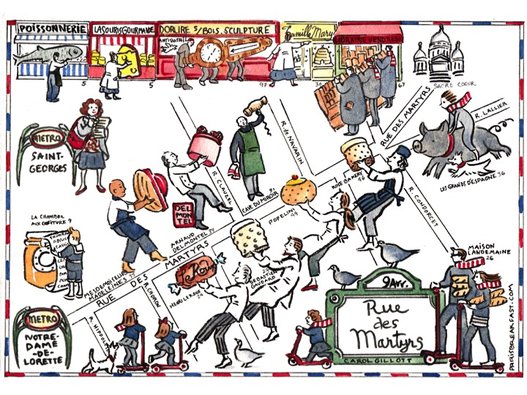

The rue des Martyrs is only half a mile long, but for me there is no better street in Paris. Northeast of the place de l'Opéra, half a mile south of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica, it packs nearly two hundred small shops, restaurants, and cafes into its storefronts. On this street, the patron saint of France was beheaded and the Jesuits took their first vows; François Truffaut filmed scenes from The 400 Blows and Pharrell Williams and Kanye West came to record at a new-age music studio.

I discovered the rue des Martyrs shortly after my husband, Andy, and I moved to Paris with our two daughters, in 2002. The street became my go-to place on Sunday mornings, when its shops are open while much of Paris is shut tight. It took me nearly a decade to move into the neighborhood. I wandered up and down the street at odd hours of the day and night. The street is all about sharing, and I bonded with its merchants, artisans, and residents. Paris finally felt like home. And thanks to this street of magic, anyone can feel at home here.

What follows is adapted from "Le Potluck," a chapter in The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue de Martyrs, to be published November 2 by W. W. Norton & Co. Copyright @ 2015 by Elaine Sciolino. The book available at W. W. Norton, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Apple, and Google Play.

Over time, I got to know so many people on the rue des Martyrs that I wanted to bring them together in a celebration of the street--the whole street. But how to do it?

Sébastien! I thought. Sébastien Guénard, the chef and owner of the bistro Miroir, at the top of the rue des Martyrs.

"Imagine a party where everyone comes together," I said. "The people at the bottom meet the people at the top."

"Let's have the party here!" he said.

Miroir used to be a Montmartre joint catering to tourists who craved cheap onion soup and garlicky escargots. Although the place looked filthy and run-down when Sébastien first saw it, it was a coup de foudre--love at first sight. "There was a side to the place that said, 'So Paris, the Paris I love, the Paris for real people,'" he recalled.

He opened Miroir in 2008 with financial backing from a businessman with a passion for reviving this part of Paris. Every morning, neighborhood residents stop in for coffee and conversation. The postman comes by, with the mail, of course, but also for a quick espresso; if he is unable to deliver a package to one of the neighbors, he leaves it at Miroir for safekeeping. Because the school nearby bans skateboards, students sometimes leave them with Sébastien until classes let out. Most afternoons, before the restaurant opens for dinner, Sébastien stands on the sidewalk, greeting everyone he knows with double-cheek kisses. Every evening, he sets aside three or four tables for friends and regulars who might show up.

Early some mornings, I venture up to this part of the rue des Martyrs. I perch at a table close to the window and watch the world go by. Catherine Mourrier, a slip of a young woman who chain-smokes and sports a brush cut with her bangs gelled upward, makes me a café crème in between washing down the sidewalks and Windexing the windows. She always brings me a small pitcher of extra-hot milk. One day she started serving me croissants.

A man who lives at the top of the street is a different kind of regular. In the old days you would have called him a wino. He carries a guitar on one shoulder and sings when the spirit moves him. He came by one morning and asked Sébastien to open his wine shop, across the street, because he wanted a bottle of red called "Forbidden Fruit." If Sébastien was annoyed, he didn't show it. He unlocked the shop door and handed the man a bottle. The man didn't pay.

"Who was that?" I asked, after he had left.

"An artist of the neighborhood," Sébastien said. "He's as sweet as can be."

"But he didn't pay you!"

"Oh, he'll pay one week or the next."

My idea for a party may have seemed whimsical, but I was determined. First, I mentioned it to everyone I knew on the street. Then I hand-delivered invitations. "Dear Martyrians," it began. "The moment I have talked about so much has finally come!" I invited them "to celebrate our rue des Martyrs, which we love so much."

I planned an old-fashioned American potluck dinner. Potluck does not exist in Paris. The French would be unhinged by its disorder: no quality (or quantity) control, no logic to the courses. Even a French family picnic in the country is more formal than an American potluck. To help bring people around, I included a note with the invitation, defining potluck as "a meal in which everyone brings something to eat or drink that can be shared. We do it often in the United States, because it's a great way to meet people around a simple meal."

We needed music, of course. I asked Pablo Veguilla, a young Puerto Rican-American opera tenor who lives just outside Paris, to join us. Pablo is an American success story. He was born poor in Chicago and raised in Orlando, Florida, where his father worked as a nursing home janitor and his mother as a hospital secretary. Yale University plucked him out of oblivion to study music at its graduate school, all expenses paid.

I suggested that he sing an aria from Puccini's La Bohème because of the opera's historical connection to the Brasserie des Martyrs, the famous nineteenth-century tavern at the bottom of the street. I told him that Henri Murger, whose book about Paris bohemian life had inspired Puccini, had been a regular there.

"Wonderful! Wonderful!" said Pablo. "I'm getting excited."

Most of the shopkeepers I invited shared Pablo's enthusiasm. Arnaud Delmontel, the baker and pastry chef, said he'd bring his signature loaf cakes. His competitor, another Sébastien (Sébastien Gaudard), an even more haute couture baker, promised a surprise. Éric Vandenberghe, the owner of the Corsican food shop, said he'd bring charcuterie. Yves and Annick Chataigner, the cheesemongers, offered Camembert and Beaufort.

I sweet-talked Justine, the daughter of the fishmonger whose shop, La Poissonerie Bleue, had closed more than a year before. By this time, Justine knew I was working on a book about the rue des Martyrs. "I am writing this book because of fish," I said. "If it weren't for you and your family's fish store, there wouldn't be a book. You are now the only representative of your family on the rue des Martyrs. Make them proud!"

read more: bridesmaid dresses